Food package labels can contain multiple forms of nutrition information to which consumers are exposed when making decisions: ingredient lists, nutrient content and health claims, functional food claims, front of package symbols and logos, how the food was produced and distributed (e.g., organic, fair trade), industry marketing, and product photos. In a study by our lab, we found that more than 50% of Canadian food products contained nutritional information in addition to the Nutrition Facts table. However, in another study we found that such nutritional information (e.g., nutrition claims) is displayed on a considerable proportion of products with a less favourable nutritional profile. Although nutrition label information is meant to help consumers make healthier food choices, the amount of label information is confusing for consumers and has been criticized as a form of industry marketing.

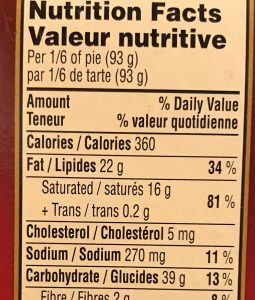

The Nutrition Facts table

The Nutrition Facts table (NFt) is mandated to appear on nearly all packaged foods sold in Canada. However, consumers have difficulty understanding the NFt – e.g. how much of a product or a particular nutrient they should eat, and how to evaluate the information, such as whether a specific level of a particular nutrient is healthy or not.

Additionally, research has demonstrated that using different serving sizes on the NFts of similar products confuses consumers and makes comparisons among similar foods difficult. A 2017 study in our lab examined this issue by comparing the serving sizes on food product NFts to national recommendations. Click here to read the study.

Front of Package (FOP) Labelling

Front of Package (FOP) labelling or comparable on-shelf systems provide a simplified summary of the healthiness of food products using symbols, logos, and designs. FOP systems are widespread in the Canadian marketplace, yet there are no specific regulations governing their use. We have identified 158 unique FOP systems on foods in the Canadian marketplace. FOP systems are proprietary (i.e., manufacturer or non-profit owned), each with a unique format and nutrient criteria. Data from our lab show that FOP systems in the Canadian marketplace may be misleading consumers:

Front of Package (FOP) labelling or comparable on-shelf systems provide a simplified summary of the healthiness of food products using symbols, logos, and designs. FOP systems are widespread in the Canadian marketplace, yet there are no specific regulations governing their use. We have identified 158 unique FOP systems on foods in the Canadian marketplace. FOP systems are proprietary (i.e., manufacturer or non-profit owned), each with a unique format and nutrient criteria. Data from our lab show that FOP systems in the Canadian marketplace may be misleading consumers:

- In one study, we found that although a large proportion of Canadian food products qualify for common third-party and manufacturer developed FOP systems, few products that meet the systems criteria are identified by their symbols. Given this, consumers cannot rely on these FOP systems to identify products of superior nutritional quality.

- In another study, we compared the amount of calories, saturated fat, sodium, and sugar in products with FOP symbols, and different FOP symbol types, to products without symbols. We found that FOP symbols are being used to market foods that are no more nutritious than foods without this type of marketing.

The government recently approved regulations mandating FOP symbols that highlights products with high levels of nutrients of public health concern such as sodium, saturated fat and/or sugars. We found that such measure could help consumers to discriminate “healthier” from “less healthy” foods and might reduce the influence that nutrition claims have on consumers. In a recent study led by our lab, we estimated the number of avoidable ischemic heart disease (IHD) and stroke incidence cases, and their associated healthcare cost and Quality-Adjusted Life Year (QALY) savings resulting from mandatory “high in” FOP labelling. Click here for an infographic of the study.

Nutrient Content Claims

Although a great deal of research and educational efforts has been focused on the Nutrition Facts table, nutrition-related claims on food labels in Canada have received little attention. Nutrient content claims are regulated by Health Canada, and are used to help consumers choose foods containing more or less of a particular nutrient. Our lab showed that nutrient content claims can be found on nearly half of Canadian food and beverage packages. The problem is that these claims are regulated on a single nutrient basis (e.g., fat) without considering the overall nutritional quality of the food (e.g., calories, sugar, sodium), which can lead to more favourable and potentially misleading evaluations of the healthfulness of the food (known as the “halo effect”). Moreover, we found that almost half of products with sugar claims contained excess free sugars and are therefore not in line with public health recommendations.

Although a great deal of research and educational efforts has been focused on the Nutrition Facts table, nutrition-related claims on food labels in Canada have received little attention. Nutrient content claims are regulated by Health Canada, and are used to help consumers choose foods containing more or less of a particular nutrient. Our lab showed that nutrient content claims can be found on nearly half of Canadian food and beverage packages. The problem is that these claims are regulated on a single nutrient basis (e.g., fat) without considering the overall nutritional quality of the food (e.g., calories, sugar, sodium), which can lead to more favourable and potentially misleading evaluations of the healthfulness of the food (known as the “halo effect”). Moreover, we found that almost half of products with sugar claims contained excess free sugars and are therefore not in line with public health recommendations.

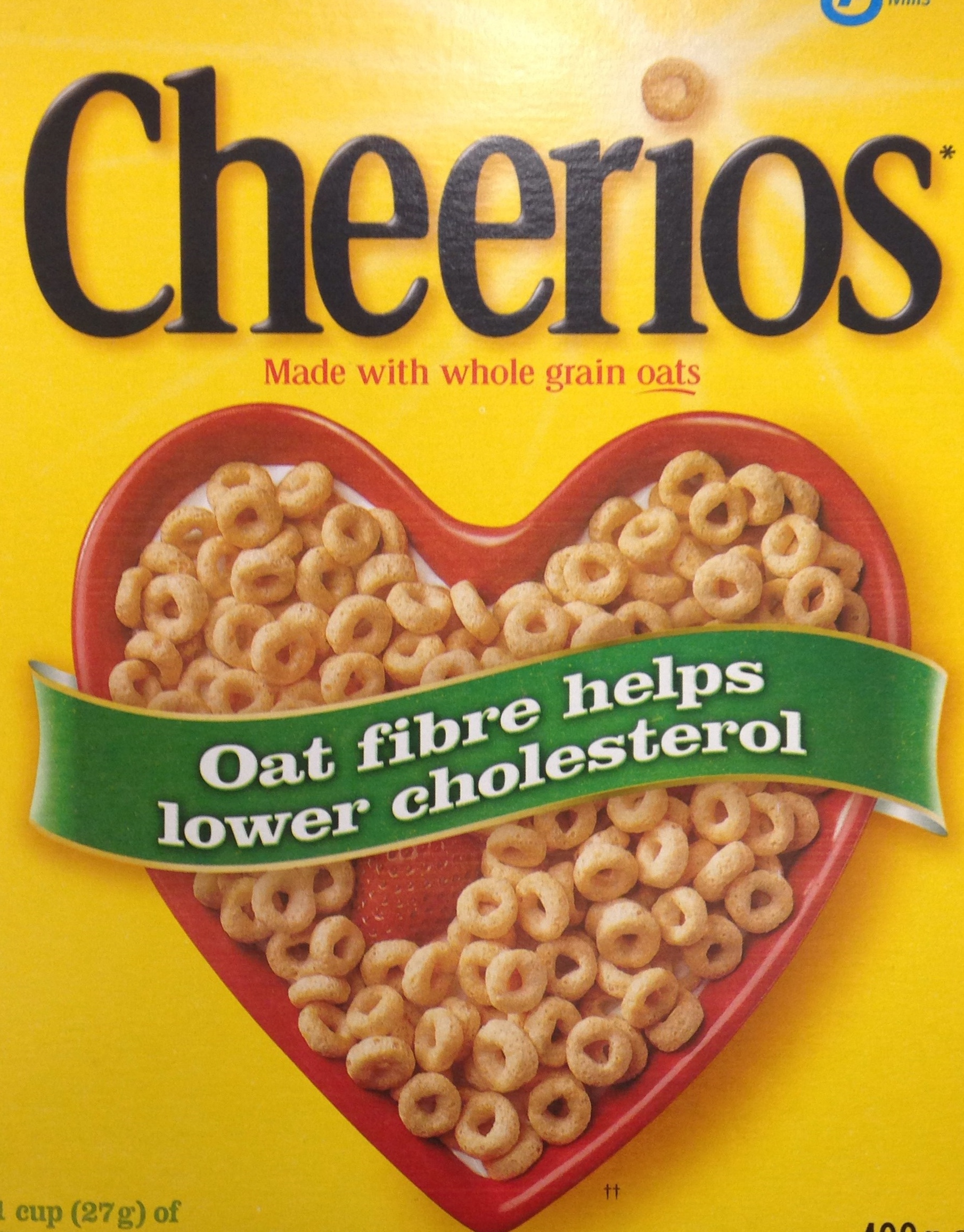

Disease Risk Reduction Claims

Disease risk reduction claims are statements that link a food or a constituent of a food to reducing the risk of developing a diet-related disease or condition (e.g., osteoporosis, cancer, hypertension, etc.) in the context of the total diet. Disease risk reduction claims are the most highly regulated claims in Canada and the wording is very prescribed. Since disease risk reduction claims are made in the context of the total diet, they have multiple claim specific criteria. This protects consumers by ensuring that the foods carrying a disease risk reduction claim do not have any other characteristics that may be counterproductive to the risk reduction of the food of interest. For example, a food that carries a disease risk reduction claim on sodium must be low in sodium as well as low in saturated fat for cardiovascular disease prevention. However, research from our lab shows that compared to most other types of claims in Canada, disease risk reduction claims are less common.

Disease risk reduction claims are statements that link a food or a constituent of a food to reducing the risk of developing a diet-related disease or condition (e.g., osteoporosis, cancer, hypertension, etc.) in the context of the total diet. Disease risk reduction claims are the most highly regulated claims in Canada and the wording is very prescribed. Since disease risk reduction claims are made in the context of the total diet, they have multiple claim specific criteria. This protects consumers by ensuring that the foods carrying a disease risk reduction claim do not have any other characteristics that may be counterproductive to the risk reduction of the food of interest. For example, a food that carries a disease risk reduction claim on sodium must be low in sodium as well as low in saturated fat for cardiovascular disease prevention. However, research from our lab shows that compared to most other types of claims in Canada, disease risk reduction claims are less common.

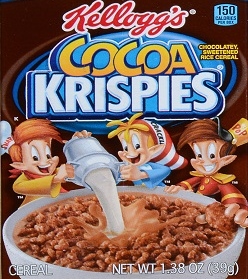

Children’s Marketing

The L’Abbé Lab is committed to conducting research to help inform and support restrictions on unhealthy food marketing to kids (M2K) – something we know to be contributing to the rising rates of childhood obesity in Canada, and around the world.

Our research has shown that M2K is pervasive and powerful on food packaging, food company websites and other platforms – but more importantly, the foods that are being M2K are significantly less healthy than foods marketed for adults. We’ve also learnt that voluntary M2K restrictions are not effective, and we support the implementation of federally mandated regulations to help foster the nutritional health of Canadian children!

For more information, see some of our publications in this area:

- Broadcast television is not dead: Child exposure to unhealthy food advertising on television in two policy environments (Ontario and Quebec).

- Advertising expenditures on child-targeted food and beverage products in two policy environments in Canada in 2016 and 2019

- Inventory of marketing techniques used in child-appealing food and beverage research: a rapid review

- Comparison of global nutrient profiling systems for restricting the commercial marketing of foods and beverages of low nutritional quality to children in Canada

- The effectiveness of voluntary policies and commitments in restricting unhealthy food marketing to Canadian children on food company websites

- Assessment of the Canadian Children’s Food and Beverage Advertising Initiative’s Uniform Nutrition Criteria for Restricting Children’s Food and Beverage Marketing in Canada

- Examining the relationship between sugars contents of Canadian foods and beverages and child-appealing marketing

- Evaluating the Canadian Packaged Food Supply Using Health Canada’s Proposed Nutrient Criteria for Restricting Food and Beverage Marketing to Children